Srijanee Adhikari

UG-III, Roll- 41

Renaissance art is the collective name given to the painting, sculpture and decorative arts that flourished in Europe between the 14th to the 17th centuries. This period saw a growth in interest towards classical learning and secular subjects. Along with Greco-Roman learning, came an interest in Platonic philosophy and the myth of the Androgyne- the original human in whom the sexes were joined together; and also in figures like Hermaphroditus- the beautiful son of Hermes and Aphrodite who became united with the nymph Salmacis in a single body. This period also saw the arrival into art of an increased awareness of nature, leading to unprecedented levels of naturalism in baroque art, and a more individualistic view of man throughout the Renaissance, which created the space for artistic portrayals of gender forms outside the normative ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ as they are imagined today. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the element of androgyny that manifests throughout the Renaissance, albeit in different contexts and for varied purposes.

The history of androgyny in visual culture is vaguely defined to say the least. However it is a recurrent subject in varied geographical and temporal contexts, and significant in the study of visual aesthetics related to gender. Androgynous figures appear in ancient representations of Egyptian deities like Kek, the personification of primordial darkness. Hindu deities often exist in multiple genders at the same time, and are depicted thus in artistic representations. For instance, the Ardhanareeswar avatar of Shiva is part-female and part-male. In various moments of the trajectory of both Islamic and Christian art, sexualised representations of human bodies were under suspicion, or forbidden. In these situations, sexual characteristics would be eliminated or at least made indistinct. This makes angels the most common androgynous figures in western art. A famous example from the Renaissance is Fra Angelico’s Annunciation (1437). This is a highly traditional Annunciation scene, expressing veneration on the part of the angel Gabriel bringing news of the birth of Christ, and a submissive humility in Mary. A gentleness is brought forth through the curves of the figures and the architecture, as well as the soft colours. Angels would be painted androgynous to indicate their lack of a sexual consciousness, and to encourage the same, presumably, in those of Christian faith. However, this androgyny was used to subversive effects in some cases, for example in Caravaggio’s Saint Matthew And The Angel (1602). The angel here is overtly feminine, and has a sexualised expression as he or she guides Saint Matthew along the pages of a book, leaning against him intimately. Caravaggio painted a different version of this after the initial one was rejected by the clerics of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome on religious and moral grounds. Interestingly, in the second version, the angel is fairly obviously masculine, and is positioned physically separate from Saint Matthew.

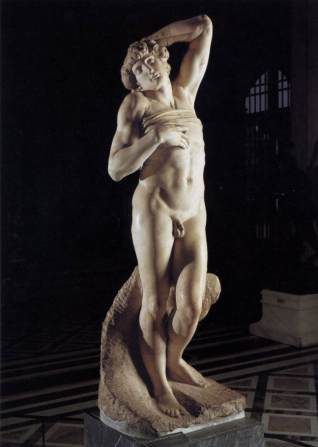

The boundaries between male and female were conceived differently in the Renaissance than they are today. Thomas Laqueur has argued that, “There was in the sixteenth century, as there had been in classical antiquity, only one canonical body, and that body was male” (Laqueur 63). The normative human body was therefore thought to be male, and female bodies were merely imperfect versions of the former. For some, women who looked most like that perfect form- that is, the male-were the most beautiful. Marsilio Ficino is known to have commented that “women who bear a masculine character” attract men easily, and “even more easily, men catch men, since they are more like men than are women”. Mario Equicola, a follower of Ficino, noted in 1525 that “the effeminate male and the manly female are graceful in almost every aspect” (Burke). Perhaps in keeping with this principle, has Michelangelo, “the unsurpassed master of portraying the male body” (Oremland 399), has often created clearly feminised male figures, notably in Dying Slave (1516) and Apollo-David (1530). Many of his Ignudi are also outstanding examples of androgynous art. These twenty male nudes framing the Biblical Histories on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in pairs of four are all “youthful and athletic”, but in relaxed poses that do not match the others (Esaak). The Ignudi 2, 3 (1511), 4 (1509) 6 (1509), 7 (1511), 10 and others have feminine facial features, hair and postures while also collectively being the epitome of attractive male physique in Renaissancce art.

In the Renaissance, there existed a tendency to identify artists with a divine power. The Divine Artist is usually thought of as a rhetorical device to encapsulate society’s admiration for the mysterious talents of the great masters (Emison 3-10). Among the artists themselves, as well, attempts to identify with Christ have been noted. In part, this is influenced by the philosophy of Imitatio Christi- “the belief professed by St.Francis and popularized in the North by Thomas à Kempis that to follow Christ is to become like him” (Koerner 76-77). Additionally, artists identified with God due to the creative process in which they reflected God’s creation of the world. Becoming godlike, that is, cultivating a mind- represented in a form- reflecting the cosmos, required the inclusion of a feminine aspect for male artists, and a masculine one for female artists. This was because some intellectual concepts foundational to mystical thought of the time differed markedly from patriarchal norms of everyday life in the Renaissance (Abrahams). It is presumably this, which led to portrayals of unmistakably feminine Christs, for example, in The Supper At Emmaus (1601) by Caravaggio, and The Last Supper (1495-1498) by Leonardo da Vinci.

No less worthy of mention is the figure of John the Evangelist in the latter painting, who is so obviously feminine, that is often thought to be Mary Magdalene. In Donatello’s Penitent Magdalene (1455), all of the Magdalen’s conventional feminine beauty has been taken away and replaced with a starkness to symbolise her spiritual progress due to years of penitence. The angularity of her features, the staccato indication of movement with her limbs, and her “surprisingly sinewy” arms, lend the sculpture an androgynous tone (Artble).

In a different vein, Donatello’s bronze David (1440s) is androgynous in the sense that the statue shows a young boy, with a lissome, elegant quality in his stance. Even though David stands with the head of the vanquished Goliath at his feet, his physique barely shows signs of the muscular development that might have been necessary to defeat this giant.

It seems as if the improbability of this victory was the goal in effeminising David, so the allusion is to divine intervention and the victory is ascribed to God, not man (ItalianRenaissance.org).

The idea of the homosexual being a masculine woman, or a feminine man has contributed to the connection of androgyny with homosexuality. Often the real, alleged or speculated homosexuality of the artists themselves are thought to be the reason behind their predilection towards painting androgynous figures. Leonardo da Vinci is said to have used his apprentice and lover Andrea Salai as a model for his famously unconventional rendition of St. John the Baptist in his painting of the same name (1513-1516). In this painting, “gentle shadows imbue the subject’s skin tones with a very soft, delicate appearance, almost androgynous in its effect, which has led to this portrayal being interpreted as an expression of Leonardo’s homoerotic leanings” (Zollner 90).

Michelangelo was thought to have a distaste for the female body due to his homosexuality, which led to a disinclination to portray female nudes in a particularly feminine way. His fresco of the Libyan Sibyl on the Sistine chapel, and his sculpture Night (1526-1531) on the tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici, are taken to testify to this effect. An artist’s sexuality however, should not be taken as a direct explanation for his artistic choices. The comparatively low availability of female models, and classical and contemporary ideals of beauty also weighed into the mix.

The figure of Cupid was a popular site of androgyny in Renaissance art. One of Parmigianino’s “most important erotic works”, Cupid Carving His Bow (1533-34) shows a clearly androgynous Cupid, with “wide, fleshy hips and stomach, narrow chest and shoulders, and more than a hint of breasts below the arm” (Thomas). Cupid here also strikes a provocative posture, much like Donatello’s bronze David, commonly associated with women and effeminate boys. Cupid’s ample curly hair is also tied up with pins after a feminine fashion. Androgynous Cupids are not uncommon in the Renaissance. Caravaggio’s Sleeping Cupid (1608) has a rather feminine lower body, and his genitalia- although male- is obscured in dramatic shadows. Amor Vincit Omnia (1602), also by Caravaggio shows a smiling youth for Cupid, who can only be described as ‘beautiful’ with his shock of voluminous reddish-brown hair, rosy cheeks and insouciant smile. There are no sexual ambiguities, with Cupid’s genitals being well-lit this time, but there are instead strong homoerotic connotations. This painting is said to be modeled after Cecco, a servant and pupil of Caravaggio’s, who was also rumoured to be his lover.

Bacchus, another classical figure linked to sexuality has been portrayed by Caravaggio as an androgynous youth, most notably in Bacchus (1595). This painting was most probably commissioned by Cardinal del Monte the year after Caravaggio entered his court.

Cardinal del Monte commissioned around 40 paintings from the artist, many depicting relatively effeminate, sexualised young men, such as in Bacchus, The Musicians (1595) and The Lute Player (1596). The Cardinal was also known to host dinner parties where young men would dress as women, and he held private concerts of castrato singers, one of whom was Pedro Montoya, speculated to be the “rather androgynous” model for The Lute Player.

Compared to that, Susan Benford finds the figures in The Musicians to be “indisputably androgynous” and cites Barbara Savina in Caravaggio tra Originali e Copie, who notes the “…dreamy, languid expressions, and smooth, oval faces with chubby cheeks, framed by soft wavy hair” of the youths. This same description can in turn be applied to Bacchus. All of these paintings, as is usual with Caravaggio, hold an erotic charge intensified by his naturalism and tenebrism. Therefore homosexual themes were intricately tied with religious aesthetic life.

The position of androgyny in Renaissance art as it has been illustrated thus far, exhibits a multiplicity of origin points and certainly that of usage, whether overt or symbolic. Androgynous representations owe their existence to revival of interest in the classical world in the Renaissance, as well as mystic lines of thought extant in the Middle Ages. Androgyny serves an amphibious function, being equally able to remove traces of sexuality and replace it with piousness, as well as to endow the artwork with an erotic drive all the more intense for its vagueness. Androgyny may have risen to popularity because of greater importance given to the male sex as the ‘normative body’, but it persisted because of the need for both the feminine and the masculine to combine and produce the ideal form created by ‘the divine artist’. Androgyny in portrayals of Biblical mythical men, like David, whose narratives indicate hypermasculinity, helps to shift attention from man’s prowess to divine intervention. At other times, figures from classical mythology like Cupid, Bacchus and Apollo receive androgynous portrayals due to their greater potential of depicting erotic themes than that of Biblical topics. Androgynous figures have often sparked conjectures and even (debatable) conclusions about homosexuality of the artists. While these paintings are definitely not enough evidence as far as the artist’s sexuality is concerned, homosexuality was fairly common in Renaissance Italy- especially Florence- and aesthetic ideals generated by prevalent sexual practices of the day are bound to affect the wider artistic consciousness. Today the wide presence of androgyny in such a crucial period of the art history canon, is of great importance to emergent academic disciplines like LGBT studies, as it dispenses valuable clues to non-heteronormative sexual and aesthetic dispositions in the Renaissance.

Works Cited

Abrahams, Simon. “Androgyny” EPPH | Every Painter Paints Himself, http://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/theme/androgyny. Accessed 6th Nov 2017.

Benford, Susan. “Caravaggio’s Paintings.” Famous Paintings Reviewed, http://www.themasterpiececards.com/famous-paintings-reviewed/bid/33037/Caravaggio-Paintings. Accessed 11th Nov 2017.

Burke, Jill. “Men with Breasts – Michelangelo’s Women 2.” Jill Burke’s Blog, 25 Feb. 2011, renresearch.wordpress.com/2011/02/25/men-with-breasts2/. Accessed 8th Nov 2017.

“Donatello’s David.” ItalianRenaissance.org, 30 Oct. 2014, http://www.italianrenaissance.org/donatellos-david/. Accessed 6th Nov 2017.

Emison, Patricia. Creating the “Divine” Artist: From Dante to Michelangelo. Brill, 2004, pp. 3-10.

Esaak, Shelley. “The Ignudi of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Frescoes .” ThoughtCo, 5 July 2017, http://www.thoughtco.com/ignudi-definition-183166. Accessed 12th Nov 2017.

Koerner. The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art. University of Chicago Press, 1993, pp. 76-77.

Laqueur, Thomas. Making Sex: Body And Gender From The Greeks To Freud. Harvard University Press, 1992, p. 63.

“Mary Magdalen.” Artble, 19 July 2017, www.artble.com/artists/donatello/sculpture/mary_magdalen. Accessed 7th Nov 2017.

Oremland, Jerome D. “Michelangelo’s Ignudi, Hermaphrodism, and Creativity.” Taylor & Francis, 6 Feb. 2017, pp.399, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00797308.1985.11823040journalCode=upsc20. Accessed 11th Nov 2017.

Thomas, Joe A. “Alchemy, Androgyny And Mannerism: Aspects Of Erotocism In The Art Of Parmigianino.” Academia.edu, http://www.academia.edu/1717579/Alchemy_Androgyny_and_Mannerism_Aspects_of_Eroticism_in_the_Art_of_Parmigianino. Accessed 9th Nov 2017.

Zollner, Frank. Leonardo Da Vinci, 1452-1519. Taschen, 2006, p. 90.

Artwork Cited

Fra Angelico. Annunciation. 1437-1446, Convent of San Marco, Florence, Italy.

Caravaggio. Amor Vincit Omnia. 1602, Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Caravaggio. Bacchus. 1595, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Caravaggio. Saint Matthew And The Angel. 1602, Poti, Georgia.

Caravaggio. Sleeping Cupid. 1608, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy.

Caravaggio. The Lute Player. 1596, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Caravaggio. The Musicians. 1595, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States of America.

Caravaggio. The Supper At Emmaus. 1601, National Portrait Gallery, London, United Kingdom.

Donatello. David. 1430-1440, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

Donatello. Penitent Magdalene. 1455, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy.

Michelangelo. Apollo-David. 1530, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

Michelangelo. Dying Slave. 1513-1516, The Louvre, Paris, France.

Michelangelo. Sistine Chapel ceiling. 1508-1512, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Michelangelo. Night. 1531, New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy.

Parmigianino. Cupid Carving His Bow. 1533-1535, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Da Vinci, Leonardo. Saint John The Baptist. 1513, The Louvre, Paris, France.

Da Vinci, Leonardo. The Last Supper. 1495-1498, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy.